The infected have defected: how viruses commandeer host transcription

A highlight of Rottenberg et al (2025) by Caroline Holley

LINK TO ARTICLE: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2025.12.01.691387v1.full.pdf

BIORXIV DOI: 10.64898/2025.12.01.691387

ORIGINAL UPLOAD DATE: December 2nd, 2025

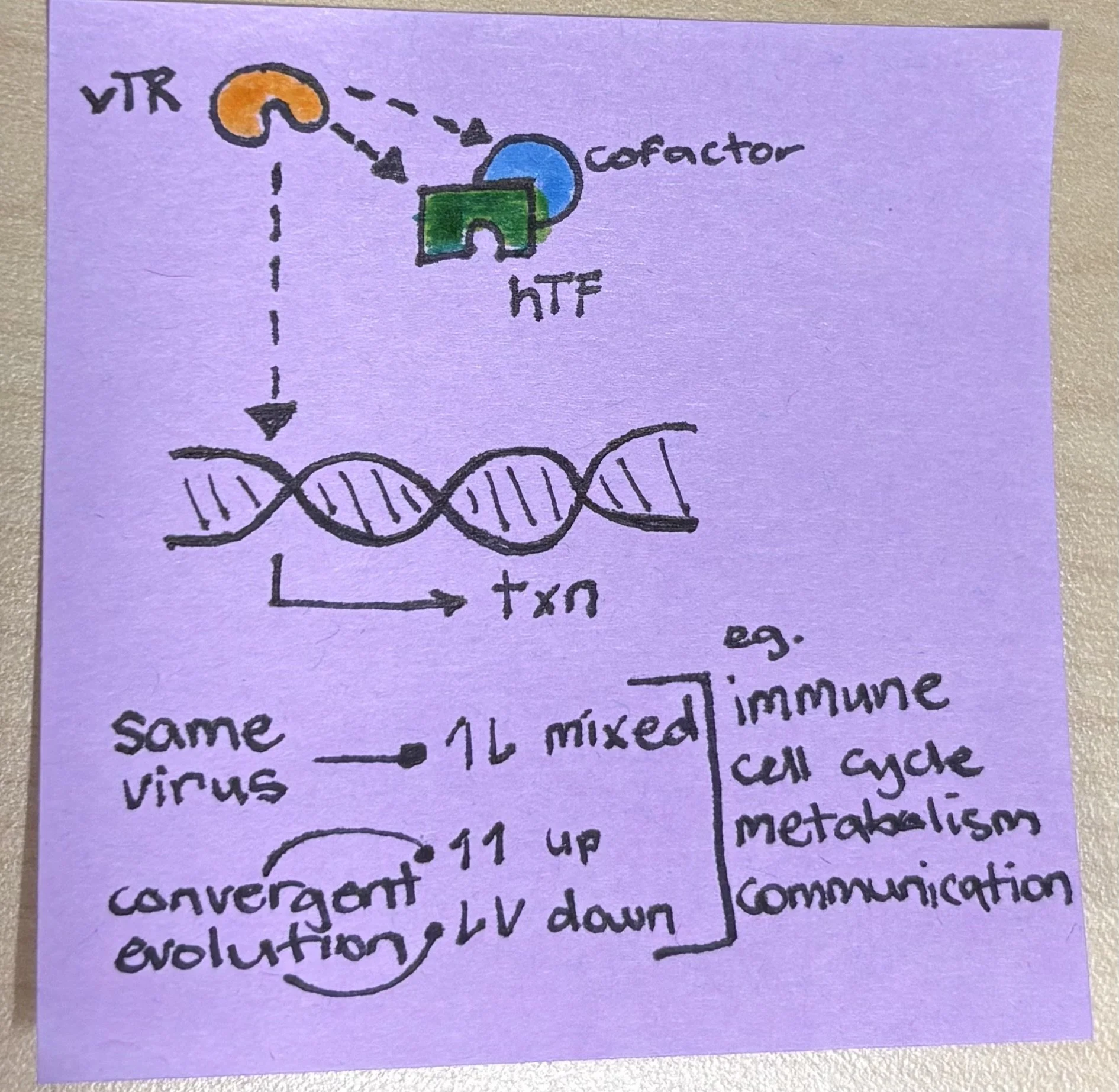

Transcriptional control underlies cell identity and responses to stimuli. Control over which genes are switched on or off defines cell lineages and further diversifies these lineages into distinct activation or deactivation states. Viruses have a small genome and, consequently, a limited proteome; their restricted suite of effector proteins must therefore be deployed efficiently to evade immune detection and hijack host machinery for survival. To this end, viruses control host transcriptional profiles through epigenetic remodelling of chromatin and histones (Locatelli & Faure-Dupuy, 2023), as well as through direct interaction with chromatin or modulation of human transcription factors (hTFs) by effectors termed viral transcriptional regulators (vTRs) (Liu et al., 2020). In a recent bioRxiv preprint, Rottenberg et al. (2025) investigate how a cohort of representative vTRs exert transcriptional control over host cells, revealing diverse strategies to rewire host transcription, including direct DNA binding, modulation of hTFs, and indirect activity via transcriptional co-regulators.

A post-it graphical abstract I drew in the time it took to finish one coffee.

The scale of the study necessitated curation of vTRs, of which over 400 are annotated (Liu et al., 2020). The authors therefore focus on 95 representative candidates from six families (the vTR1.0 cohort) and use a blend of unbiased and targeted assays to capture the extent and modality of transcriptional control. The primary unbiased approach was bulk RNA barcoding and sequencing (BRB-seq) of HEK293T cells transiently expressing individual vTRs. Some results aligned with known family-specific mechanisms; for example, Retroviridae upregulated DNA repair pathways, consistent with their integration into the host genome. Poxviridae vTRs also upregulated DNA repair genes, despite replicating in the cytoplasm rather than the nucleus (Schramm & Locker, 2005). As large double-stranded DNA viruses, this machinery may support viral replication or genome stability, or the cluster may include genes unrelated to DNA repair. Herpesviridae and Papillomaviridae upregulated cell–cell communication pathways, potentially facilitating long-term persistence or viral spread. As expected, immune-related genes were major vTR targets, whereas relatively few metabolism-related genes were affected, despite well-established infection-associated metabolic rewiring. Viruses may instead modulate metabolism through transcription-independent mechanisms, such as molecular mimicry of metabolites (Girdhar et al., 2021). Comparisons between vTRs from the same virus revealed substantial diversity and, in some cases, contradictory regulation of host genes, suggesting that some viruses invest limited resources into a small number of critical pathways. Conversely, convergent regulation by evolutionarily distinct vTRs points to shared selective pressures across viral families.

As the previous assays were performed in uninfected cells, the authors next assessed how these effects change in an infected environment. Because it is not feasible to infect cells with every parental virus corresponding to the vTR1.0 cohort, BRB-seq was repeated in HEK293T cells infected with Sendai virus (SeV). Although SeV is non-pathogenic in humans, it activates antiviral pathways and imposes a distinct transcriptional signature (Mandhana & Horvath, 2018). Surprisingly, infection status did not substantially alter most vTR-driven transcriptional profiles, with changes largely confined to immune-related pathways. The authors do not state whether SeV encodes its own vTRs or how these might interact with the vTR1.0 cohort. A reassuring observation was that Herpesviridae vTRs induced neuronal programme-associated transcription in SeV-infected cells, consistent with the lifelong neuronal persistence of this family.

Having established that vTR1.0 contains potent transcriptional rewiring agents and reveals both intraviral diversity and cross-lineage convergence, the authors next dissected the mechanisms by which vTRs hijack transcription. DNA promoter baits from dysregulated pathways were assayed using enhanced yeast one-hybrid approaches, alongside paired assays testing vTR–hTF synergy. Approximately one fifth of vTRs directly bound human promoters, while others acted cooperatively or antagonistically with hTFs. The authors focused subsequent analyses on regulators of oncogenes, interferon pathways, and IL-1 signalling. Selected vTRs were further examined by ATAC-seq, revealing virus-specific chromatin-remodelling strategies. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) EBNA3A induced the greatest chromatin accessibility, whereas adenovirus B E4ORF6/7 targeted regions associated with the tumour suppressor p53. These viruses were likely highlighted due to their high prevalence. Together, these data reinforce the conclusion that vTRs employ diverse transcriptional strategies. The nature of vTR activity was further refined using a mammalian one-hybrid assay, which demonstrated that vTRs—particularly from Herpesviridae and Adenoviridae—are generally stronger transcriptional regulators than selected hTFs. This is intuitive, given the small viral proteome and narrow window before immune detection. Stratification by expression timing revealed lower activity vTRs during latency, followed by a sharp increase from early to late infection, an intriguing trend warranting further investigation. A complementary yeast two-hybrid screen against the human ORFome identified 132 novel protein–protein interactions involving 33 vTRs and 67 hTFs, underscoring the multifunctionality of relatively few vTRs and aligning with their strong transcriptional activity.

Consistent with earlier findings, vTRs from the same virus could exert contradictory effects on similar pathways. EBV vTRs displayed mixed behaviour, whereas human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) vTRs cooperated on similar pathways. Reanalysis of protein–protein interactions revealed that some host targets were multivalently engaged by vTRs from a single virus, including transcriptional co-regulators and proteins without known transcriptional roles, such as MAP1S (a microtubule-associated protein). While HPV is not previously characterised to target MAP1S, similar interactions have been reported for HIV and HBV, likely outside the curated vTR library. Endoplasmic reticulim (ER)-resident SEC61B was also identified as a target of several EBV vTRs, notable given its interaction with SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a to perturb ER function (Lee et al., 2023). These findings suggest that viruses may occasionally devote substantial resources to a limited set of pathways, potentially using indirect or as-yet unclear mechanisms of transcriptional control. Extending these analyses across unrelated viral lineages, sequence homology emerged as an imperfect predictor of function. Some vTRs with low sequence similarity exhibited convergent targeting, whereas highly homologous vTRs, such as HSV-1 and HSV-2 US1, exerted opposing effects on extracellular signalling genes. Homologous vTRs also differed in their behaviour under SeV infection and in their interaction profiles, reinforcing the theme of diversity and unpredictability in viral transcriptional regulation.

Finally, the authors examined links between vTRs and human disease. Viral infection is known to increase the risk of cancer, neuroinflammation, and autoimmunity. Mining GWAS data revealed that some vTRs target disease-associated motifs, including HHV-1 vTR interactions with locations containing Parkinson’s disease-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Herpesviruses have been linked to Parkinson’s disease in proteomic studies of infected neurons (Li et al., 2025), and one rheumatoid arthritis-associated SNP in the HHV-1 interactome is also linked to systemic lupus erythematosus, consistent with the central role of HLA-DQB1 in autoimmunity. These observations provide a brief but intriguing glimpse into how vTRs may contribute to disease-associated outcomes of infection.

In sum, this work highlights the remarkable diversity and complexity of vTR activity. Understanding how these programmes operate across infection stages and cell tropisms, particularly for viruses like Herpesviridae that transition between epithelial and neuronal environments, will be an important direction for future research. While additional infection-based validation would strengthen the conclusions, this study delivers both a high-level framework for viral transcriptional control and a rich set of novel leads for the host–pathogen cell biology community.

AI USE DISCLOSURE

I drafted and edited this highlight myself. I used ChatGPT5.2 (Plus) to perform a final grammar and tone check (prompt: “Check this text for grammatical errors and fix where necessary. Suggest replacements where necessary to achieve a professional tone. Do not edit the content otherwise”), and to condense text (prompt: “suggest a 10% reduction in text”). I sparingly used ChatGPT5.2 (Plus) to further explain unfamiliar field-specific jargon (e.g. prompt: “Explain the connection specificity index as simply as possible”). I also prompted it to perform searches for further information on SNPs highlighted in the final figure (prompt: “Take these SNP identifiers [identified from Figure 7] and retrieve any disease associations from GWAS data (provide exact sources) other than hypothyroidism and rheumatoid arthritis”.

REFERENCES

Bjornevik, K., Cortese, M., Healy, B. C., Kuhle, J., Mina, M. J., Leng, Y., Elledge, S. J., Niebuhr, D. W., Scher, A. I., Munger, K. L., & Ascherio, A. (2022). Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein–Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science, 375(6578), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj8222

Camacho-Soto, A., Faust, I., Racette, B. A., Clifford, D. B., Checkoway, H., & Nielsen, S. S. (2021). Herpesvirus infections and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegenerative Diseases, 20(2–3), 97. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512874

Fernandez, J., Portilho, D. M., Danckaert, A., Munier, S., Becker, A., Roux, P., Zambo, A., Shorte, S., Jacob, Y., Vidalain, P. O., Charneau, P., Clavel, F., & Arhel, N. J. (2014). Microtubule-associated protein 1 promotes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 intracytoplasmic routing to the nucleus. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290(8), 4631–4646. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.613133

Girdhar, K., Powis, A., Raisingani, A., Chrudinova, M., Huang, R., Tran, T., Sevgi, K., Dogru, Y. D., & Altindis, E. (2021). Viruses and metabolism: The effects of viral infections and viral insulins on host metabolism. Annual Review of Virology, 8, 373–391. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-091919-102416

Guan, Y., Li, J., Sun, B., Xu, K., Zhang, Y., Ben, H., Feng, Y., Liu, M., Wang, S., Gao, Y., Duan, Z., Zhang, Y., Chen, D., & Wang, Y. (2024). HBx-induced upregulation of MAP1S drives hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and migration via a MAP1S/Smad/TGF-β1 loop. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 281, 136327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136327

Lee, Y.-B., Jung, M., Kim, J., Charles, A., Christ, W., Kang, J., Kang, M.-G., Kwak, C., Klingström, J., Smed-Sörensen, A., Kim, J.-S., Mun, J.-Y., & Rhee, H.-W. (2023). Super-resolution proximity labeling reveals antiviral protein networks and structural changes induced by SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins. Cell Reports, 42(8), 112835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112835

Li, Z., Martin, N. P., Epstein, J., Chen, S.-H., Hao, Y., Ramos, D. M., Andersh, K. M., Jarreau, P., Weller, C., Nalls, M. A., Pantazis, C. B., Ferrucci, L., Cookson, M. R., Singleton, A. B., Qi, Y. A., & Yakel, J. L. (2025). Proteomic analysis of endemic viral infections in neurons offers insights into neurodegenerative diseases. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.03.17.643709

Liu, X., Hong, T., Parameswaran, S., Ernst, K., Marazzi, I., Weirauch, M. T., & Fuxman Bass, J. I. (2020). Human virus transcriptional regulators. Cell, 182(1), 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.023

Locatelli, M., & Faure-Dupuy, S. (2023). Virus hijacking of host epigenetic machinery to impair immune responses. Journal of Virology, 97(9). https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00658-23

Mandhana, R., & Horvath, C. M. (2018). Sendai virus infection induces expression of novel RNAs in human cells. Scientific Reports, 8, 16815. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35231-8

Raj, P., Rai, E., Song, R., Khan, S., Wakeland, B. E., Viswanathan, K., Arana, C., Liang, C., Zhang, B., Dozmorov, I., Carr-Johnson, F., Mitrovic, M., Wiley, G. B., Kelly, J. A., Lauwerys, B. R., Olsen, N. J., Cotsapas, C., Garcia, C. K., Wise, C. A., … Wakeland, E. K. (2016). Regulatory polymorphisms modulate HLA class II expression and promote autoimmunity. eLife, 5, e12089. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.12089

Schramm, B., & Locker, J. K. (2005). Cytoplasmic organisation of poxvirus DNA replication. Traffic, 6(10), 839–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00324.x

Xiao, Q., Liu, Y., Li, T., Wang, C., He, S., Zhai, L., Yang, Z., Zhang, X., Wu, Y., & Liu, Y. (2025). Viral oncogenesis in cancer: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 10(1), 151. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02197-9